Speculation and commodity prices

In the paper entitled “A Bitter Brew? Futures Speculation and Commodity Prices", Maarten van der Molen and myself try to answer a question that has gained a lot of attention in recent years: has speculation contributed to rising commodity prices?

You can view a lecture on the topic here.

Synopsis

In the paper, we investigate whether supply and demand of coffee futures by so-called non-commercials - parties that do not buy or sell coffee on the spot market for coffee - has contributed to changes in coffee prices. We find that this is indeed the case, and our findings show that the effect has been an increase in coffee prices. Speculation is not the most important factor that explains prices: supply side developments (changes in agricultural productivity, frosts and droughts, etc.) are the most important. However, the impact of speculation - when it occurs - is significant, both statistically and economically.

What makes this paper different?

There are three key reasons why we think our paper provides a contribution to the discussion.

First, we use a new approach to measuring the possible impact of futures speculation on spot commodity prices. We use a non-parametric model that is very flexible. What this means is that, rather than estimating the average impact (or lack thereof) of speculation on commodity prices, we use a model that is informative, even if there is no average impact, but only an impact in extreme situations. We think this is important because our theoretical model, as well as the available literature, suggests that if there is an impact, it may very well be 'spiky'. If that is the case, then other, more mainstream methods may not be able to pick up these effects.

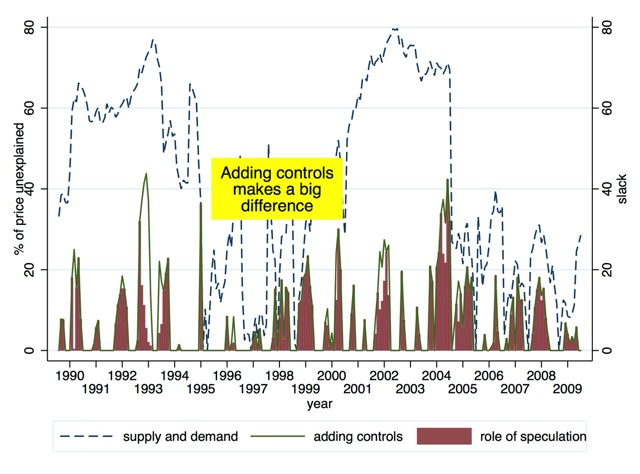

Second, we use both financial data and demand and supply related information. We think, and we show, that this is important. The most important impact on prices comes, in our study, not from speculation, but from supply-side changes, related to frosts and droughts, agricultural productivity changes, etc. However, once we control for this, there is still a serious effect from speculation. Moreover, our analysis shows that in order for speculation to have maximum impact, a sort of 'perfect storm' has to exist, where supply and demand related factors play an important role.

Third, we have put a lot of effort in supplying the reader with an extended series of robustness tests. The paper is accompanied by a long appendix (of equal length as the paper) that contains details of all our additional tests. They are summarized in a special section in the paper. As part of these robustness tests, we compare our results to what is achieved when we use more traditional measurement methods, and we explain (also empirically) the differences in results.

What makes this paper different?

There are three key reasons why we think our paper provides a contribution to the discussion.

First, we use a new approach to measuring the possible impact of futures speculation on spot commodity prices. We use a non-parametric model that is very flexible. What this means is that, rather than estimating the average impact (or lack thereof) of speculation on commodity prices, we use a model that is informative, even if there is no average impact, but only an impact in extreme situations. We think this is important because our theoretical model, as well as the available literature, suggests that if there is an impact, it may very well be 'spiky'. If that is the case, then other, more mainstream methods may not be able to pick up these effects.

Second, we use both financial data and demand and supply related information. We think, and we show, that this is important. The most important impact on prices comes, in our study, not from speculation, but from supply-side changes, related to frosts and droughts, agricultural productivity changes, etc. However, once we control for this, there is still a serious effect from speculation. Moreover, our analysis shows that in order for speculation to have maximum impact, a sort of 'perfect storm' has to exist, where supply and demand related factors play an important role.

Third, we have put a lot of effort in supplying the reader with an extended series of robustness tests. The paper is accompanied by a long appendix (of equal length as the paper) that contains details of all our additional tests. They are summarized in a special section in the paper. As part of these robustness tests, we compare our results to what is achieved when we use more traditional measurement methods, and we explain (also empirically) the differences in results.

What do our results look like?

In the paper, we focus on explaining the impact of speculation on the coffee price. The main reason: we have excellent data for the coffee market, both regarding demand and supply related factors as well as regarding financial market data. Since we think that is crucial for this type of an analysis to match 'real world' data with financial data, we opted to focus for now on coffee. In the near future, we will extend our analysis to other commodities.

Why coffee?

A quick look at the slides below show our main results. If you want to know more, check the paper!

Where do we stand in the public debate?

We have tried, in our paper, to be as objective as possible. Put simply, when we started this research our impression of the two sides of the debate can be summarized as follows: on the one hand there are those who claim that speculation must be driving prices, on the other hand there are those who claim that speculation cannot be driving prices. Whereas the former group uses mostly anecdotal evidence and has for a long time failed to provide robust empirical evidence, the latter group often assumes that there can be no link between futures speculation and commodity prices, and bases its analyses on mean-variance techniques, which - as we explained above - we think is not without problems.

Our paper is not the only recent work that tries to walk a middle ground and attempts to formally test for a linkage between futures and spot prices of commodities. In the paper, we provide a short overview of some of these recent studies.

Who is the evil genius driving up commodity prices?

In the many discussions regarding a possible effect of speculation on commodity prices (especially food prices), those that think (and/or find) that there is an effect see what has happened as yet another example of how some intentionally get rich at the expense of many. This is not what our paper claims, for a number of reasons. First, we argue - and find evidence, to some extent - that it is the mechanical way in which these futures indices work that contributes to the effect they sometimes have. Second, futures indices themselves are used mainly by institutional investors, who use them as a cheap way of diversifying our pensions, avoiding the high bonuses that make many more actively managed investment vehicles so expensive. Third, there is no evidence of strategic behavior of investors in these futures indices that is anything like what is going on elsewhere (think for example of land grabbing). Thus, although we think that the evidence we present in our paper is cause for a serious further discussion and (see below) possible measure to limit the effects of this kind of speculation, we do not think it is appropriate to point fingers in one single direction.

What do we think should be done, based on our findings?

Non-academic readers may be disappointed at our first recommendation: more research needs to be done on this matter.We think that our results provide a convincing cases that futures speculation has affected the coffee price. However, we also think that similar analyses are required to establish to what extent the same thing has happened on other commodities markets.

We do have some additional thoughts though. First, our results - although preliminary, point at an interesting, and somewhat discomforting role for oil: it is not only the biggest commodity in the futures indices, but also an 'input' in the production of many commodities (as fuel, through fertilizers, etc.). As a result, when the oil price goes up, the price of other commodities goes up (through its role as an input). But, we find preliminary evidence that when the futures price of oil goes down, the price of the other commodities can still go up, since more momney is shifted into the futures of those commodities, which in turn can increase their prices.

Second, we think the role of the futures indices should be discussed. We do not advocate banning these indices, as some others have suggested, since we think that non-commercial parties on the futures markets also provide liquidity, and it is very difficult if not impossible to decide how much the share of these non-commecials should be reduced (we have some ideas about this, but no results yet). But we are concerned about the mechanical way in which these indices tend to go long-long: put simply, these indices are not only increasing the market for futures, but they are mainly active on one side of the market (= demand). That is in itself not a problem: for every party going long on the futures market (= buying) some other party has to go short (= sell). However, the futures indices, in contrast to most other parties, are not trading based on the fundamentals for individual commodities: changes in the demand and/or supply of coffee do not have an effect on how much coffee futures commodity indices are buying. That is why, we think, these indices can have an - unintended - effect on prices.

Sep 2, 2012